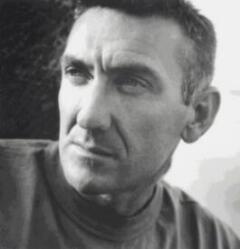

Scoring for Liverpool: Interview with writer Kevin Sampson

by Anna Battista

"Music. Business. Two words which should never live side by side," writes

Kevin Sampson at some point of his novel, Powder: An Everyday Story of

Rock'N'Roll Folk (Jonathan Cape). The ex-manager of the Liverpool-based band The

Farm couldn't be further away than he is at present from the world of

music business. With four proper novels out, Awaydays, Powder,

Leisure and the latest Outlaws, plus a non-fiction book, Extra Time

(all published by Jonathan Cape in Great Britain) and a fifth novel in the

works, Sampson can happily look back upon his career in the music business

as something that happened in a distant past. But there is something else,

something that, according to him happened in an equally distant past, which

is still influencing his life: it is called writing.

"Music. Business. Two words which should never live side by side," writes

Kevin Sampson at some point of his novel, Powder: An Everyday Story of

Rock'N'Roll Folk (Jonathan Cape). The ex-manager of the Liverpool-based band The

Farm couldn't be further away than he is at present from the world of

music business. With four proper novels out, Awaydays, Powder,

Leisure and the latest Outlaws, plus a non-fiction book, Extra Time

(all published by Jonathan Cape in Great Britain) and a fifth novel in the

works, Sampson can happily look back upon his career in the music business

as something that happened in a distant past. But there is something else,

something that, according to him happened in an equally distant past, which

is still influencing his life: it is called writing.

"Possibly I started writing in my mother's womb!" he exclaims, before explaining, "Seriously, I lived in a land of make-believe when I was a kid. I was always telling very elaborate lies and making up stories. That led directly to writing. I always loved writing at school. My first paid work was for a review of The Cult in NME when I was 18, then I started writing for The Face and carried on reviewing the Liverpool scene for Sounds and NME."

Sampson's career as a novelist officially started in 1998, when his first novel, Awaydays, was finally published, "I first wrote Awaydays many years ago, at the time I was writing for NME and The Face," he recalls, "The Face published a condensed version of it, but the only publisher I sent it off to, Penguin, rejected it. This made me lose heart that I could ever be a 'real' writer and I concentrated on writing film scripts, instead. When I read Trainspotting I thought that maybe the world of publishing was now ready for a book like Awaydays. This time I sent it to an agent, Nick Hornby's agent, actually, and she said 'Yes' immediately. Three weeks later I had a two books deal with Cape. Readers loved Awaydays, it was quite raw and violent, but the public liked its passion and insight. Powder was a huge success: people are fascinated by the excesses of famous people, especially actors and rock stars, and this confirmed their worst fears! Leisure was not loved by my readers. Fans of Awaydays wanted more action, fans of Powder expected more sex, more drugs, more comedy. In fact Leisure is quite a subtle study of relationships, so it felt lost between the previous two books. I love Leisure, I think it will find its readership eventually. Outlaws has been very highly praised. The Awaydays fans absolutely love it. What annoys me is that reviewers refer to it as 'a return to form', as though Leisure was a crock of shit. Ah well - can't please everybody always, hey?"

But, which is Sampson's fave book among his own titles? "Hmmm,

probably Awaydays," he claims, "because it's the first and I still

associate it with the excitement of the new. That was a wonderful time,

writing the book, getting an agent and finding out that it was going to be

published by Cape. They are the coolest publisher in the U.K. They publish

all my heroes - Irvine Welsh, Ian McEwan, Tom Wolfe, Don DeLillo, etc. But

I think Outlaws is probably my best book. It's totally gripping from

start to finish - frighteningly convincing, too. I think all my books have

an element of me in them. In Awaydays there's bits of me in both the

Carty and Elvis characters. In Powder definitely, not really Wheezer, but

some of the other characters. I won't say who. And, although I am a lithe

and gorgeous specimen, I have much in common with overweight, insecure

Pasternak in Leisure. Having said that, none of the books is 'my' story.

I've used personal experiences and observations as a point of departure.

For me the reward of being a writer still stands in the thrill of seeing a

story that was born in my head sitting on the shelf of a bookstore - right

next to Salinger! It's good when people write to you and tell you that your

work has affected them in some way. And it's good to have something to

leave behind, when you're gone. That may sound morbid, but it marks you

out. So few people have the chance to have a legacy. My books are mine."

But, which is Sampson's fave book among his own titles? "Hmmm,

probably Awaydays," he claims, "because it's the first and I still

associate it with the excitement of the new. That was a wonderful time,

writing the book, getting an agent and finding out that it was going to be

published by Cape. They are the coolest publisher in the U.K. They publish

all my heroes - Irvine Welsh, Ian McEwan, Tom Wolfe, Don DeLillo, etc. But

I think Outlaws is probably my best book. It's totally gripping from

start to finish - frighteningly convincing, too. I think all my books have

an element of me in them. In Awaydays there's bits of me in both the

Carty and Elvis characters. In Powder definitely, not really Wheezer, but

some of the other characters. I won't say who. And, although I am a lithe

and gorgeous specimen, I have much in common with overweight, insecure

Pasternak in Leisure. Having said that, none of the books is 'my' story.

I've used personal experiences and observations as a point of departure.

For me the reward of being a writer still stands in the thrill of seeing a

story that was born in my head sitting on the shelf of a bookstore - right

next to Salinger! It's good when people write to you and tell you that your

work has affected them in some way. And it's good to have something to

leave behind, when you're gone. That may sound morbid, but it marks you

out. So few people have the chance to have a legacy. My books are mine."

"I think I was excited, genuinely thrilled by football violence for the first time when all the Woodchurch rats, Elvis in the thick of them, ran into the Blackburn blokes and starting peppering them, swarming all over them, digging them and butting them. For a second Blackburn backed off down the terracing, unsure whether it was okay to hit back at a bunch of kids. Elvis' crew carried on, really giving it to them, picking up the lumps of concrete and broken masonry that littered the back of the Cowshed, savaging the Blackburn contingent. I was gripped." Kevin Sampson, Awaydays

Set at the end of the '70s, Awaydays competes for its main themes,

football fans and football violence, with a stack of novels about the

football scene and hooligans, from Irvine Welsh's Marabou Stork

Nightmares to John King's trilogy, The Football Factory, Headhunters

and England Away. Apart from Awaydays, Samspon tackled the football

fandom issue also in Extra Time, a report about Sampson and friends'

experiences following Liverpool around, during the 1997/98 season. Which

is, according to Sampson, the best book about football fans? "There isn't

much actual fiction about football gangs - most of it is the reminiscences

of retired football hooligans. Of the novels that deal the subject of

football fans I'd say Awaydays is the best; of the non-fiction titles,

Nick Hornby's Fever Pitch is almost as good as Extra Time. Football violence was considered as the "English disease" in the '80s: in

particular, 1985 marked the year of another typical Thatcher war, the war

of the government against the hooligan menace. As Matthew Collin remembers

in his history of the Ecstasy and Acid House culture, Altered State, the

following years, 1986-90, were characterised by further initiative taken by

the government, such as the membership scheme, while the battle against

hooliganism continued.

Set at the end of the '70s, Awaydays competes for its main themes,

football fans and football violence, with a stack of novels about the

football scene and hooligans, from Irvine Welsh's Marabou Stork

Nightmares to John King's trilogy, The Football Factory, Headhunters

and England Away. Apart from Awaydays, Samspon tackled the football

fandom issue also in Extra Time, a report about Sampson and friends'

experiences following Liverpool around, during the 1997/98 season. Which

is, according to Sampson, the best book about football fans? "There isn't

much actual fiction about football gangs - most of it is the reminiscences

of retired football hooligans. Of the novels that deal the subject of

football fans I'd say Awaydays is the best; of the non-fiction titles,

Nick Hornby's Fever Pitch is almost as good as Extra Time. Football violence was considered as the "English disease" in the '80s: in

particular, 1985 marked the year of another typical Thatcher war, the war

of the government against the hooligan menace. As Matthew Collin remembers

in his history of the Ecstasy and Acid House culture, Altered State, the

following years, 1986-90, were characterised by further initiative taken by

the government, such as the membership scheme, while the battle against

hooliganism continued.

"The government is no closer to understanding the phenomenon now than it was 20 years ago," Sampson claims, joking "in spite of Tony Blair's Ralph Lauren tennis shirts!" And yet, during the '90s there seemed to be something in the air that would have changed the behaviour of football fans, it was called ecstasy. Once the love pill got to the terraces, unlikely events started happening: football fans from rival teams were seen hugging each other instead of literally killing each other as usually happened. Indeed, at the beginning of the '90s and, in particular, after Italia '90, the World Cup Finals, things started to change, though the surveys registered still a latent menace from hooliganism. Researcher and writer Steve Redhead called the 1989-90 season, a season swept by marijuana and E, the "Winter of Love" in contrast with the "Summer of Love" experienced in clubs, parties and raves all over Great Britain. "No Alla Violenza" T-shirts were successful and the slogan was showed on the final frame of The Beats International's video for their hit "Won't Talk About It," while New Order, Manchester's acclaimed band, provided the World Cup song "World in Motion," considered as containing anti-hooligan lyrics. Asked by the Melody Maker if he thought that the rave culture had influenced the terraces, The Farm's Peter Hooton answered that it was "definitely true."

Did Sampson ever find himself on the terraces in the early '90s thinking that football hooliganism had really come to a stop thanks to E? "I really thought it had gone for good, sure," Sampson admits, "it wasn't just Ecstasy, either, although that definitely had an impact. I mean, some teams just hate each other. Look at Manchester United and Manchester City - they carried on battling right throughout the Ecstasy years. But yeah, it got to the stage where you were going to Leeds United and Chelsea and you were drinking in the bars near the ground and it seemed like that period of horrific pre-match trouble had never happened. It's a little bit tense again at the moment. It's not back to the bad old days, but there's tension in the air." Terrace-fashion-rave: at the end of the 1980s, during the early 1990s, as Matthew Collin underlines, the three elements strengthened in a trio and spawned a fabulous fame for DJs such as Andrew Weatherall, Paul Oakenfold and Terry Farley, associated with the fanzine Boy's Own and treated as football stars: who are today's football stars? "Farley, Oakenfold and Weatherall's agents!" he jokes, "Club owners like Palumbo (Ministry of Sound) and Barton (Cream) have a fabulously excessive lifestyle now, too. They've created empires out of places where people went to dance. Amazing."

"Elvis and I are perhaps the most fashion-obsessed of The Pack, which is a pretty fucking well-dressed crew by anybody's standards. Most of us have wedges or side-partings and wear Samba or Stan Smith trainies, Lois jeans and cardigans … We look the part, and everyone knows it." Kevin Sampson, Awaydays

Awaydays tackled, among the other things, an aspect of football passion, the love for designer clothes: hooligans were often characterised by a sort of dress-code. During the early '90s, the fanzine The End used to trace the story of football fashion underlining the differences between one city and another and the labels favoured by particular football supporters. "The era of Awaydays was the dawning of that period when soccer fans in England dressed in designer labels," Sampson underlines, "Liverpool was the first team to dress like this, and Liverpool supporters still try to look different, if only by dressing from head to toes in Lacoste! But today pretty well all football fans dress the same. On the whole they are better dressed. In the Awaydays era you could spot a fan from Birmingham, say, by their ludicrous wide trousers, just as you could spot a Liverpool supporter by their wedge haircut. But in general the majority of fans look okay these days." But what happened to football fanzines, are the days of The End or Boy's Own definitely over? "I think the Internet has taken away the function of fanzines like that. There are netzines like 'Terrace Retro' and 'Partizan' that are quite reminiscent of 'The End', but I do believe the days of selling Xerox-copied home-made magazines in the pubs and clubs is over," Sampson concludes before morbidly adding, "Excuse me - I have to wipe my tears away…" Since we are talking about football, it would be impossible not to ask Sampson which is the best football team of all times. "Best team, France 1984. Best player, Michel Platini: I thought he was unbelievable - better than Cruyff, better than Georgie Best, better than Maradona. As you see, I like midfielders. Zinedine Zidane is getting close to Platini, though."

"Elvis and I saw Joy Division playing an Amnesty benefit at Eric's back in May… Joy Division blew us away. Ian Curtis threw so much angst and demented energy into his show that he collapsed after five or four songs. They couldn't have been on stage more than half and hour, but it was completely stunning. And they just kept getting better." Kevin Sampson, Awaydays

Sampson's short story "Two Star", appeared on the anthology Vox'n'Roll

edited by Richard Thomas, which includes among the others, stories by

Patrick McCabe, Lana Citron, Nicholas Blincoe, Irvine Welsh and Stella

Duffy. The anthology is connected with the Vox'n'Roll nights that have been

taking place in an Islington bar since 1995: during these events writers

are invited to read short sections of their work, interspersed by some

music they themselves have chosen for the occasion. Also Sampson took part

in these readings, "For Awaydays I chose Leonard Cohen's 'Famous Blue

Raincoat', Dr. Amontilado's 'Reason For Living' and Joy Division's 'Love

Will Tear Us Apart', that seemed to fit the Carty/Elvis love story

perfectly. I didn't do a Vox'n'Roll for Powder, but for Leisure I

played 'Holes' by Mercury Rev, 'The Winner Takes It All' by Abba and

'Marquee Moon' by Television. Each song has a direct resonance with the

stories and characters. I absolutely love short stories, I think it's an

art-form all of its own and I think I am nowhere near mastering it. I love

writing short stories - it's how I started - and I'm constantly inspired by

little things that happen in life. A good story has to take its reader into

worlds they do not know, involve them enough to make them want to stay and

deliver an epiphany that makes them sad to say goodbye. A good writer only

needs the ability to deliver all three. I'm sure that one day I'll collect

enough good stories to release a volume. Not as the next book, though! That

one's called Clubland, it comes out in the summer in the U.K. and it's

pretty sleazy." And meanwhile, while you're waiting for the new novel to

come out, Sampson gives us a reliable reading list: "Everybody should read

Raul Nunes' Sinatra sometime. It was re-published as The Lonely Hearts

Club. It's a beautiful, funny and very wise book set in the ramblas of

Barcelona. If you like tougher works of fiction, Chump Change and Mooch

by Dan Fante are superb. And Sons & Lovers by D.H. Lawrence. That lot

should keep you busy."

Sampson's short story "Two Star", appeared on the anthology Vox'n'Roll

edited by Richard Thomas, which includes among the others, stories by

Patrick McCabe, Lana Citron, Nicholas Blincoe, Irvine Welsh and Stella

Duffy. The anthology is connected with the Vox'n'Roll nights that have been

taking place in an Islington bar since 1995: during these events writers

are invited to read short sections of their work, interspersed by some

music they themselves have chosen for the occasion. Also Sampson took part

in these readings, "For Awaydays I chose Leonard Cohen's 'Famous Blue

Raincoat', Dr. Amontilado's 'Reason For Living' and Joy Division's 'Love

Will Tear Us Apart', that seemed to fit the Carty/Elvis love story

perfectly. I didn't do a Vox'n'Roll for Powder, but for Leisure I

played 'Holes' by Mercury Rev, 'The Winner Takes It All' by Abba and

'Marquee Moon' by Television. Each song has a direct resonance with the

stories and characters. I absolutely love short stories, I think it's an

art-form all of its own and I think I am nowhere near mastering it. I love

writing short stories - it's how I started - and I'm constantly inspired by

little things that happen in life. A good story has to take its reader into

worlds they do not know, involve them enough to make them want to stay and

deliver an epiphany that makes them sad to say goodbye. A good writer only

needs the ability to deliver all three. I'm sure that one day I'll collect

enough good stories to release a volume. Not as the next book, though! That

one's called Clubland, it comes out in the summer in the U.K. and it's

pretty sleazy." And meanwhile, while you're waiting for the new novel to

come out, Sampson gives us a reliable reading list: "Everybody should read

Raul Nunes' Sinatra sometime. It was re-published as The Lonely Hearts

Club. It's a beautiful, funny and very wise book set in the ramblas of

Barcelona. If you like tougher works of fiction, Chump Change and Mooch

by Dan Fante are superb. And Sons & Lovers by D.H. Lawrence. That lot

should keep you busy."

"To think that he could walk away from music was a folly. Most of it he could cheerfully dump - the packaged, niche-marketed, antiseptic dreck which constituted so much of his popmart world. But there would always be moments like this. There would continue to be, for always, that one track which transcends everything." Kevin Sampson, Powder

Kevin Sampson's second novel, Powder, was very aptly dedicated to Seymour

Stein, and revolved around the world of the music business. The plot

follows the life of talented Keva, lead-singer and guitarist with the band

The Grams. Keva is positive that one day he'll make it and release a

smashing hit that will go straight to number one. The novel starts with him

reading the NME and finding that his worst enemy and lead-singer with

hateful and useless band Sensira is on the cover of the Bible of Rock. As

the classics teach, talent is stimulated by emulation. In some cases envy,

in others admiration, impels it to surpass, and Keva, James, Tony and

Beano, AKA The Grams, helped by their manager Wheezer and by the man behind

their label, Guy (on a quest for his personal Holy Grail, that is "one

track which transcends everything"), stimulated by emulating their hateful

rivals, start their rise to success. The novel follows the career of the

band from the release of the first single, throughout the gigs, the sex

gratuitously offered by the groupies, the video shootings in Ibiza, the

contracts and the endless tours in the U.K., in Europe and in the States

that will bring them to fame and to sell millions of their album, Powder.

Kevin Sampson's second novel, Powder, was very aptly dedicated to Seymour

Stein, and revolved around the world of the music business. The plot

follows the life of talented Keva, lead-singer and guitarist with the band

The Grams. Keva is positive that one day he'll make it and release a

smashing hit that will go straight to number one. The novel starts with him

reading the NME and finding that his worst enemy and lead-singer with

hateful and useless band Sensira is on the cover of the Bible of Rock. As

the classics teach, talent is stimulated by emulation. In some cases envy,

in others admiration, impels it to surpass, and Keva, James, Tony and

Beano, AKA The Grams, helped by their manager Wheezer and by the man behind

their label, Guy (on a quest for his personal Holy Grail, that is "one

track which transcends everything"), stimulated by emulating their hateful

rivals, start their rise to success. The novel follows the career of the

band from the release of the first single, throughout the gigs, the sex

gratuitously offered by the groupies, the video shootings in Ibiza, the

contracts and the endless tours in the U.K., in Europe and in the States

that will bring them to fame and to sell millions of their album, Powder.

The Grams build their future in a world that is much more used to consume the artistic talent and transform it, through some perverted kind of alchemy, into money: "At all times," Sampson writes, "all bands and artists were product and their treatment reflected their marketability … The music business wasn't fair." So, if the theory of gravity is always right and therefore what goes up has to come down, the Grams' eventual ruin is imminent. The end of their career is signalled by Keva's fast growing ego who sacks manager and best friend, Wheezer. As a whole Powder is an endless entertaining journey through the world of rock'n'roll, highly detailed, full of crazed humanity and debauched fooleries, two characteristics proper to human beings, but also full of immorality and demented excess, two characteristics typical of any band on this planet. Above all this is a novel full of one and only truth: the glittering and sparkling world of the music biz is a huge pile of stinking shit by which press officers, managers, music journalists, directors and musicians are inevitably attracted like dirty flies.

That said, would Sampson ever go back to manage bands? "No way!", he scarily exclaims. "When I finished managing The Farm I got the chance to manage Stone Roses among others, but everybody who asked me, I said no. I never wanted to manage a band in the first place. Of the new bands, I like Starsailor and The Coral (they live by me!), but no, I wouldn't want to go through that madness again. My liver has only just started breathing again. I still keep in touch with members of The Farm as they're my best friends. I go to the Liverpool matches with Peter and Roy (we'll be in Barcelona for the game at the Camp Nou), and I go drinking with Steve. Carl is playing in a Clash tribute band called 'Radio Clash': he's achieved his life's ambition after all these years! We're all going to see them play next week. Can't wait!" Though Sampson isn't interested anymore in managing bands, he still loves music, "Hmmm, I have so many favourites, but if I had to nominate just one it's Sigur Ros. 'Ny Batteri' is far and away my favourite track of recent years."

It's easy to wonder if there is a particular event of the days in which Sampson managed The Farm, that showed him how much the music biz is fake. "Too many to list. It's not worse than real life, though, we all encounter fair weather friends, don't we?" So who are the nicest people in the music world, if they actually exist? "The caterers. All touring bands hire full-time caterers to prepare their special, pampered, ridiculous meals. 'I specifically asked for guinea fowl, not wood pigeon!!' how the cooks tolerate them I don't know. Either they are all resurrected saints or they're slipping powders in the rock stars' food that they know will make them impotent. Whatever, the cuisine crew always had a smile on their face." While describing The Grams' manager Wheezer, Sampson underlines that he wears "C&A" clothes: wonder if that's the only difference between him and the original Sampson, "Where d'you get that idea from?" he enquires, "I live in C&A clothes! The only difference between myself and the godlike Wheezer Finlay is that he gets more girls than I do."

"The snowy peaks of the highest ranges were now frozen below them, tiny and precise. He was startled, overcome and totally unafraid. The Mercury Rev song 'Holes' came into his head. Serene and disembodied, it scored Shaun's sky-high feelings sublimely." Kevin Sampson, Leisure

After exploring the world of football fandom in Awaydays and the world of

corrupted rock'n'roll in Powder, Kevin Sampson literally moved to more

relaxed shores - those of Costa Del Sol, where Leisure, his third novel,

the story of seven days in the life of a bunch of British tourists (seven

days which will eventually change their life forever), takes place.

"Leisure was inspired by a normal holiday photograph," Sampson explains,

"In the foreground, a group of happy people, in the background, a couple

whose faces are distorted by the violence of their argument. It was like a

Pieter Breughel painting. It started me thinking about the way couples go

on holiday to heal their broken relationships, when more often the sun and

the wine bakes the cracks wide open and leaves them out to dry." At a

certain point of the novel, Shaun, one of the characters goes paragliding

and while experiencing the thrilling excitement of this sport, he thinks

about Mercury Rev's song "Holes", "Music constantly inspires my thought and

dreams," Sampson claims, "all kinds of music, from Gorecki to Radiohead.

But once I start writing I need total silence."

After exploring the world of football fandom in Awaydays and the world of

corrupted rock'n'roll in Powder, Kevin Sampson literally moved to more

relaxed shores - those of Costa Del Sol, where Leisure, his third novel,

the story of seven days in the life of a bunch of British tourists (seven

days which will eventually change their life forever), takes place.

"Leisure was inspired by a normal holiday photograph," Sampson explains,

"In the foreground, a group of happy people, in the background, a couple

whose faces are distorted by the violence of their argument. It was like a

Pieter Breughel painting. It started me thinking about the way couples go

on holiday to heal their broken relationships, when more often the sun and

the wine bakes the cracks wide open and leaves them out to dry." At a

certain point of the novel, Shaun, one of the characters goes paragliding

and while experiencing the thrilling excitement of this sport, he thinks

about Mercury Rev's song "Holes", "Music constantly inspires my thought and

dreams," Sampson claims, "all kinds of music, from Gorecki to Radiohead.

But once I start writing I need total silence."

"What we're talking is drugs. Class-A drugs. It's me that brings them in and it's me that drops them off. The only time I can't see the fucking gear is when it's all dressed up in the boot of my vehicle. I've done it up all sorts. I've taken fucking massive packages of caper round in the boot, done up like a kid's birthday present." Kevin Sampson, Outlaws

Sampson's latest novel Outlaws is the story of a group of supposed

friends and of a scam they plan to do during the Christmas holidays. Drugs

and guns seem to be the main ingredients that spice up the relationship

that regulates the lives of Ged, Moby and Ratter. Outlaws is mysteriously

dedicated to what Sampson calls a "dream team, DF and CD", but he doesn't

seem that keen to reveal who they are as, as he claims, "It's a secret!"

though he's totally keen on telling us more about the novel "The world of

Outlaws is a tough, vivid contemporary world. It's quite male dominated,

too - full of violence, greed, selfish sex, habitual drug-taking, plotting,

scheming and treachery. It's about gangs, too, though this time the gangs

are full of grown men. Like Awaydays it gives and insight into some of

the reasons why some men behave the way they do. But Awaydays has a

subtlety and a femininity to it that would have been out of place in

Outlaws. Outlaws is a much more brutal book, though more exciting than

Awaydays, I think. Criminality has always existed in Liverpool.

Liverpool, London and Amsterdam control the drug supply of western Europe -

this forms the backdrop to Outlaws, the idea of new, ruthless drug gangs

pushing aside the older gangs like the Brennans. Gun culture is definitely

on the up in Liverpool, but that's true of every major European city, I

think. In Awaydays and Outlaws I used the slang - not to excess,

though. It's important to get the rhythm of the streets if you're writing

about the streets. For what regards the characters, well, we're not really

supposed to sympathise with any of them. I've tried to give a glimpse of

their lives and show the way they see themselves, but none of them is

especially endearing. Ged Brennan has certain qualities, he's quite noble

in a twisted kind of way, but I wouldn't want to live next door to him.

Other than that you'd never, ever get burgled…"

Sampson's latest novel Outlaws is the story of a group of supposed

friends and of a scam they plan to do during the Christmas holidays. Drugs

and guns seem to be the main ingredients that spice up the relationship

that regulates the lives of Ged, Moby and Ratter. Outlaws is mysteriously

dedicated to what Sampson calls a "dream team, DF and CD", but he doesn't

seem that keen to reveal who they are as, as he claims, "It's a secret!"

though he's totally keen on telling us more about the novel "The world of

Outlaws is a tough, vivid contemporary world. It's quite male dominated,

too - full of violence, greed, selfish sex, habitual drug-taking, plotting,

scheming and treachery. It's about gangs, too, though this time the gangs

are full of grown men. Like Awaydays it gives and insight into some of

the reasons why some men behave the way they do. But Awaydays has a

subtlety and a femininity to it that would have been out of place in

Outlaws. Outlaws is a much more brutal book, though more exciting than

Awaydays, I think. Criminality has always existed in Liverpool.

Liverpool, London and Amsterdam control the drug supply of western Europe -

this forms the backdrop to Outlaws, the idea of new, ruthless drug gangs

pushing aside the older gangs like the Brennans. Gun culture is definitely

on the up in Liverpool, but that's true of every major European city, I

think. In Awaydays and Outlaws I used the slang - not to excess,

though. It's important to get the rhythm of the streets if you're writing

about the streets. For what regards the characters, well, we're not really

supposed to sympathise with any of them. I've tried to give a glimpse of

their lives and show the way they see themselves, but none of them is

especially endearing. Ged Brennan has certain qualities, he's quite noble

in a twisted kind of way, but I wouldn't want to live next door to him.

Other than that you'd never, ever get burgled…"

We've got to know Sampson as journalist, manager and writer, but we still haven't talked about his abilities in organising literary festivals, indeed he was involved in the organisation of the Liverpool on the Wall Festival. "I was invited as a speaker at the first WOW in 1999," he remembers, "I loved the unique philosophy of the festival - it was anti-promotion. The organisers just invited people they liked, or who they knew would provoke a reaction. So, the next year I got involved on the organising panel. I brought in Howard Marks, Bill Drummond, Roddy Doyle, Stella Duffy, people like that. I've had to cut back a bit this year as I've been finishing this new book." During the latest WOW, Interchill, a community-based internet resource centre presented a short film based on a Kevin Sampson script, but our author has also applied himself at this difficult trade. "I've written the screenplay for Awaydays and loved that whole process. It's quite difficult to distance yourself from your own work and deconstruct it in such a way that you can re-create it in a slightly different form for the screen. Of all the books though, Outlaws is crying out to be made into a movie. Mike Hodges, the director of Get Carter and Croupier, has written to express his interest. That would be perfect. Get Carter is one of my favourite films, and its world is not so different from Outlaws."

This looks like 'his' day, we might proclaim, paraphrasing one of The Farm's songs: Sampson will be celebrating the release of his sixth book this summer, some of his stuff might soon be turned into a movie and if this weren't enough, Liverpool has also entered the Quarter Finals of the Euro Champions League. Who knows, you might even be able to meet Kevin Sampson at some book festival near you sooner or later. Or at some gigs, perhaps. Or, more aptly, on the terraces, mingled with the rest of the crowd.

{Special thanks to Kevin Samspon for his patience in answering my questions.}

Copyright (c) 2005 erasing clouds |

Kevin Sampson pic by Ken Grant. |