Cinematic Pleasures: Let's Get Lost

by j.d. lafrance

Why do we find ourselves fascinated by people who seem to have it all - good looks, loads of talent, and that special sort of something that elevates them to iconic status - yet they can never seem to handle this power. Inevitably something, whether it is a self-destructive streak from within or outside influences, brings them crashing back to earth. It is this tragic arc that we find so fascinating ó people who seem to have everything and then throw it all away. Such is the case with Bruce Weberís absorbing documentary-portrait Letís Get Lost (1988), which focuses on jazz trumpeter Chet Baker, a man who epitomized what Pauline Kael labeled a ďself-destructive beauty.Ē

Why do we find ourselves fascinated by people who seem to have it all - good looks, loads of talent, and that special sort of something that elevates them to iconic status - yet they can never seem to handle this power. Inevitably something, whether it is a self-destructive streak from within or outside influences, brings them crashing back to earth. It is this tragic arc that we find so fascinating ó people who seem to have everything and then throw it all away. Such is the case with Bruce Weberís absorbing documentary-portrait Letís Get Lost (1988), which focuses on jazz trumpeter Chet Baker, a man who epitomized what Pauline Kael labeled a ďself-destructive beauty.Ē

The filmís title originates from the first Chet Baker album Weber bought at the age of 16 in a Pittsburgh record store. This purchase started a life-long obsession with the manís music and career. This gives you an indication of the attitude that Weber has towards Baker. Essentially a two-hour love letter to its subject (Weber spent about a million dollars of his own money on the film), Letís Get Lost assembles a strange and wonderful group of Baker fans, ranging from ex-associates to ex-wives, to paint a fascinating portrait of a man who was as self-absorbed in life as he was talented on record and stage.

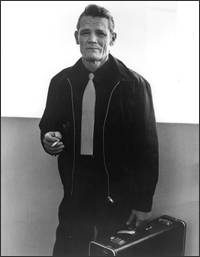

Weberís film traces the manís career from the 1950s, when he was in his prime, playing with jazz greats like Charlie Parker and Gerry Mulligan, to the 1980s, when he had become a skid row junkie unable to get a decent gig. By juxtaposing these two decades, Weber presents a sharp contrast between the younger, handsome Baker ó the statuesque idol who resembled a dreamy mix of James Dean and Jack Kerouac ó to what he became, ďa seamy looking drugstore cowboy cum derelict,Ē as J. Hoberman put it in his Village Voice review. Baker was the archetype of ďbeat,Ē encompassing the full range of this term throughout his whole life, from its connotations of coolness in the Ď50s when he was young and handsome to its inferences of world-weariness in the Ď80s when he was old and burnt out.

Letís Get Lost begins near the end of Bakerís life, on the sun-kissed beaches of Santa Monica, and ends at the glitz and glamour of the Cannes Film Festival. Weber uses these moments in the present as bookends to the historic footage contained in the bulk of the film. This documentation ranges from vintage photographs by William Claxton in 1953 to appearances on The Steven Allen Show and kitschy, low budget Italian films Baker did for quick money. And even though much of Bakerís past is captured only in still photos, Weber and his director of photography, Jeff Preiss, use creative camera techniques to energize these static pictures in a way that almost brings them lovingly to life.

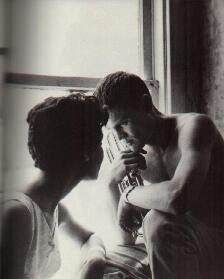

And who better to do a film about a self-centered icon like Chet Baker than Bruce Weber, an internationally reknowned photographer famous for his fetishistic Calvin Klein ads? Weber clearly has an eye for the kind of vacuous beauty that you see not only in those pretentious ads but that is also reflected in Bakerís blank stare. One of the joys of watching Letís Get Lost is the lush cinematography of Jeff Preiss, who films the whole picture in grainy black and white film stock. His camera alternates between hand-held shots and gliding pans of Baker and his world that only enhance the dreamy mood of Weberís film.

And who better to do a film about a self-centered icon like Chet Baker than Bruce Weber, an internationally reknowned photographer famous for his fetishistic Calvin Klein ads? Weber clearly has an eye for the kind of vacuous beauty that you see not only in those pretentious ads but that is also reflected in Bakerís blank stare. One of the joys of watching Letís Get Lost is the lush cinematography of Jeff Preiss, who films the whole picture in grainy black and white film stock. His camera alternates between hand-held shots and gliding pans of Baker and his world that only enhance the dreamy mood of Weberís film.

This romantic mood, complemented by Bakerís enchanting voice and music, enhances the filmís soundtrack. His slow, seductive singing has been described as ďlike being sweet-talked by the void,Ē and this is certainly true of Bakerís more recent recordings where he really sounds tired, as if each breath is going to be his last. This feeling is demonstrated towards the end of the film when Baker performs Elvis Costelloís ďAlmost BlueĒ at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival. Itís a quiet sort of song and as soon as Baker begins to sing the rest of the world seems to disappear, leaving only this ravaged, emaciated shadow of his former self, who still has an entrancing presence and the power to captivate an audience.

Weberís first film was the 1987 documentary Broken Noses, about the life of a youthful, Bakeresque Portland boxer named Andy Minsker and his even younger proteges. Weber dedicated the film to Baker and even featured some of the manís music in the film. However, the origins of Letís Get Lost go back even further, to the winter of 1986, when the photographer met Baker for the first time. Weber convinced the musician to do a photo shoot and what was originally to be nothing more than a three-minute film. The final two-hour result is the cinematic equivalent of a Chet Baker song: a slow, dreamy trip that captivates you with its breathless beauty and yet shows the manís unsavory side as well: the downward spiral into drug addiction and the string of failed marriages. Itís a bittersweet love story ó much like many of Bakerís songs. Weber summed up these mixed feelings best in an interview when he said that ďthe whole team felt the same way about him. We wanted to save him. We wanted to get him a house, a car. But he really didnít want to be saved. And after a while, we gave up trying. When you live and survive as long as he did, you get a little bit paranoid about whatís going on. If Chet had any anger, it was because of the pressures with people wanting him to do things he didnít want to do.Ē

On May 13, 1988, a few months before Letís Get Lost was to be released, Chet Baker died mysteriously after a fall from a second-floor window in an Amsterdam hotel near the drug dealersí part of town. That night, all the jazz clubs in Paris were silent. Weberís film went on to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Feature Documentary and played at film festivals all over the world. But first and foremost, Letís Get Lost remains one of the best visual documents of Chet Bakerís tragic life and career.

Copyright (c) 2005 erasing clouds |

|