Cinematic Pleasures: Rumble Fish

by j.d. lafrance

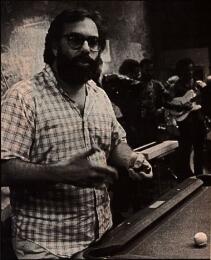

History remembers Francis Ford Coppola's, Rumble Fish (1983) as a film that was booed by its audience when it debuted at the New York Film Festival and in turn was viciously crucified by North American critics upon general release. It's too bad because it is such a dreamy, atmospheric film that works on so many levels. It is also Coppola's most personal and experimental project--on par with the likes of Apocalypse Now (1979). From the epic grandeur of The Godfather films to the excessive Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992), Coppola has pushed the boundaries, both on-screen and off. He has almost gone insane, contemplated suicide, and faced bankruptcy on numerous occasions, but he always bounces back with another intriguing feature that is visually stunning to watch. And yet, Rumble Fish curiously remains one of Coppola's often overlooked films. This may be due to the fact that it refuses to conform to mainstream tastes and stubbornly challenges the Hollywood system with its moody black and white cinematography and non-narrative approach.

History remembers Francis Ford Coppola's, Rumble Fish (1983) as a film that was booed by its audience when it debuted at the New York Film Festival and in turn was viciously crucified by North American critics upon general release. It's too bad because it is such a dreamy, atmospheric film that works on so many levels. It is also Coppola's most personal and experimental project--on par with the likes of Apocalypse Now (1979). From the epic grandeur of The Godfather films to the excessive Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992), Coppola has pushed the boundaries, both on-screen and off. He has almost gone insane, contemplated suicide, and faced bankruptcy on numerous occasions, but he always bounces back with another intriguing feature that is visually stunning to watch. And yet, Rumble Fish curiously remains one of Coppola's often overlooked films. This may be due to the fact that it refuses to conform to mainstream tastes and stubbornly challenges the Hollywood system with its moody black and white cinematography and non-narrative approach.

Rumble Fish alienated former head of production for Paramount, Robert Evans, who "remembers being shaken by how far Coppola had strayed from Hollywood. Evans says, 'I was scared. I couldn't understand any of it.'" Apparently, many critics agreed, as typified by Vincent Canby's review in The New York Times. He wrote, "Rumble Fish is not a success, but there is something deserving of attention in its failure. Mr. Coppola thinks BIG, which is better than not thinking at all." Rumble Fish was tossed off as a self-conscious art film. However, now that some time has passed, I see it as a movie clearly ahead of its time: a stylish masterpiece that is obsessed with the notion of time, loyalty, and family. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of Coppola's film is that it presents a world that refers to the past, present, and future while remaining timeless in nature.

Right from the first image Rumble Fish is a film that exudes style and ambience. It opens on a beautiful shot of wispy clouds rushing overhead, captured via time lapse photography to the experimental, percussive soundtrack that envelopes the whole film. This creates the feeling of not only time running out, but also a sense of timelessness.

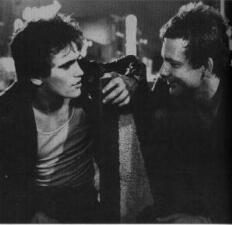

Adapted from an S.E. Hinton novel of the same name, Rumble Fish explores the disintegrating relationship between two brothers, Rusty James (Matt Dillon) and the Motorcycle Boy (Mickey Rourke). The older brother derives his name from his passion: stealing motorcycles for joyrides. The film begins with the Motorcycle Boy absent, perhaps gone for good, while Rusty James tries to live up to his brother's reputation: to act like him, to look like him, and, ultimately, to be him. Rusty James' brother is viewed as a legend in the town as he was the first leader of a gang and also responsible for their demise.

Much like Harry Lime in The Third Man (1949), the Motorcycle Boy is initially physically absent, but his presence is felt everywhere--from the shots of graffiti on walls and signs that read, "The Motorcycle Boy Reigns," to the numerous times he is referred to by characters. This quickly establishes him as a figure of mythic proportions. When the Motorcycle Boy finally does appear--during a fight between Rusty James and local tough, Biff Wilcox (Glenn Withrow)--it is a dramatic entrance on a motorcycle like Marlon Brando in The Wild One (1953). This appearance marks a significant change in the film. We begin to see the world through the eyes of the Motorcycle Boy, almost as if the whole film is taking place in his head.

Consequently, Rumble Fish is shot entirely in black and white to simulate his colour blindness. We even begin to hear the world like he does: voices sound echoey, disembodied, with his own heartbeat threatening to drown everything else out. It is this existential worldview that makes the Motorcycle Boy a tragic character. The rest of the film explores his attempts to come to grips with this outlook and his relationship with Rusty James, who views him as a hero--a label that the older sibling has never been able to accept.

Consequently, Rumble Fish is shot entirely in black and white to simulate his colour blindness. We even begin to hear the world like he does: voices sound echoey, disembodied, with his own heartbeat threatening to drown everything else out. It is this existential worldview that makes the Motorcycle Boy a tragic character. The rest of the film explores his attempts to come to grips with this outlook and his relationship with Rusty James, who views him as a hero--a label that the older sibling has never been able to accept.

Coppola wrote the screenplay for Rumble Fish with Hinton on his days off from shooting The Outsiders (1982). As the filmmaker said in an interview, "the idea was [that] The Outsiders would be made very much in the style of that book, which was written by a 16-year old girl, and would be lyrical and poetical, very simple, sort of classic. The other one, however, Rumble Fish, which she wrote years later, was more adult, kind of Camus for teenagers, this existential story." Coppola even went so far as to make the films back-to-back, retaining much of the same cast and crew.

Actual filming began on July 12, 1982 on many of the same Tulsa, Oklahoma sets used in The Outsiders. The attraction to Rumble Fish, for Coppola, was the "strong personal identification" he had with the subject matter: a young brother hero-worships his older, intellectually superior sibling. Coppola realized that the relationship between Rusty James and the Motorcycle Boy mirrored his own connection to his brother, August. It was an older, more experienced August who introduced Francis to film and literature. Coppola always felt like he was living in the shadow of his brother and saw the film as a "kind of exorcism, or purgation" of this relationship.

As always, Coppola assembled an impressive ensemble cast for his film. From The Outsiders, he kept Matt Dillon, Diane Lane, Glenn Withrow, William Smith and Tom Waits, while casting actors like Mickey Rourke and Vincent Spano, who were overlooked for roles in the film for one reason or another. They all fill out their roles admirably, but Mickey Rourke in particular is mesmerizing as the Motorcycle Boy.

As always, Coppola assembled an impressive ensemble cast for his film. From The Outsiders, he kept Matt Dillon, Diane Lane, Glenn Withrow, William Smith and Tom Waits, while casting actors like Mickey Rourke and Vincent Spano, who were overlooked for roles in the film for one reason or another. They all fill out their roles admirably, but Mickey Rourke in particular is mesmerizing as the Motorcycle Boy.

To get Rourke into the mindset of his character, Coppola gave him some books written by Albert Camus and a biography of Napoleon. "There's a scene in there when I'm walking down the bridge with Matt; and I'd try and stylise my character as if he was Napoleon," the actor remembers. The Motorcycle Boy's look was patterned after Camus complete with trademark cigarette dangling out of the corner of his mouth--taken from a photograph of the author that Rourke used as a visual handle. He portrays the character as a calm, low key figure that seems to be constantly distracted as if he is in another world or reality. Rourke "Methodically" conceived the Motorcycle Boy as being "an actor who no longer finds his work interesting." To this end, he uses subtle, little movements and often cryptic phrases that only he seems to understand.

This feeling is further enforced by the two brothers' alcoholic father, played brilliantly by Dennis Hopper in a surprisingly low key performance. He describes the Motorcycle Boy perfectly when he says that "he is merely miscast in a play. He was born in the wrong era, on the wrong side of the river. With the ability to be able to do anything that he wants to do and finding nothing that he wants to do." Rourke's Motorcycle Boy is almost embarrassed by the myth that surrounds him, that threatens to drown him. He openly rejects it when he says, "I'm tired of all that Robin Hood, Pied Piper bullshit. You know, I'd just as sooner stay a neighbourhood novelty if it's all the same to you... If you're gonna lead people, you have to have somewhere to go." It is this reluctance to embrace his legendary reputation that gives the Motorcycle Boy an element of humanity that was not in the novel.

Not only did Coppola assemble a talented cast of actors, but he also gathered an impressive crew to create the images and the proper mood to compliment them. The striking black and white photography of the film's cinematographer, Stephen Burum, lies in two main sources: the films of Orson Welles and German cinema of the 1920's. Welles' influence is particularly apparent in one scene where the Motorcycle Boy and Steve bring a wounded Rusty James home. While Steve and Rusty James talk in the background, the Motorcycle Boy looms into a close-up, as if the lens were a mirror in which he was admiring himself. He is clearly a character who suffers from what one critic called, "fatal narcissism," a trait common in many of Welles' films. This deep focus shot (a favourite of Welles) shows how far removed the Motorcycle Boy is from his brother and from everyone. He is like a mirror, impenetrable and impossible to read as Steve observes, "I never know what he's thinking." This scene harkens back to Welles' masterpiece, Citizen Kane (1941), which used the deep focus technique to give characters that look of "fatal narcissism," to live a doomed existence.

Not only did Coppola assemble a talented cast of actors, but he also gathered an impressive crew to create the images and the proper mood to compliment them. The striking black and white photography of the film's cinematographer, Stephen Burum, lies in two main sources: the films of Orson Welles and German cinema of the 1920's. Welles' influence is particularly apparent in one scene where the Motorcycle Boy and Steve bring a wounded Rusty James home. While Steve and Rusty James talk in the background, the Motorcycle Boy looms into a close-up, as if the lens were a mirror in which he was admiring himself. He is clearly a character who suffers from what one critic called, "fatal narcissism," a trait common in many of Welles' films. This deep focus shot (a favourite of Welles) shows how far removed the Motorcycle Boy is from his brother and from everyone. He is like a mirror, impenetrable and impossible to read as Steve observes, "I never know what he's thinking." This scene harkens back to Welles' masterpiece, Citizen Kane (1941), which used the deep focus technique to give characters that look of "fatal narcissism," to live a doomed existence.

Before filming started, Coppola ran regular screenings of old films during the evenings to familiarize the cast and in particular, the crew with his visual concept for Rumble Fish. Most notably, Coppola showed Anatole Litvak's Decision Before Dawn (1951), the inspiration for the film's smoky look, and Robert Wiene's Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919), which became Rumble Fish's stylistic prototype. Coppola's extensive use of shadows (some were painted on alley walls for proper effect), oblique angles, exaggerated compositions, and an abundance of smoke and fog are all hallmarks of these German Expressionist films. Godfrey Reggio's Koyaanisqatsi (1983), shot mainly in time-lapse photography, motivated Coppola to use this technique to animate the sky in his own film. The result is an often surreal world where time seems to follow its own rules.

Coppola envisioned a largely experimental score to compliment his images. He began to devise a mainly percussive soundtrack to symbolize the idea of time running out. As Coppola worked on it, he realized that he needed help from a professional musician. And so he asked Stewart Copeland, drummer of the musical group The Police, to improvise a rhythm track. Coppola soon realized that Copeland was a far superior composer and let him take over. The musician proceeded to record street sounds of Tulsa and mixed them into the soundtrack with the use of a Musync, a new device at the time, that recorded film, frame by frame on videotape with the image on top, the dialogue in the middle, and the musical staves on the bottom so that it matched the images perfectly. One only has to see Copeland's evocative score matched with the film's exquisite imagery to realize how well the musician understood Coppola's intentions.

Rumble Fish is a rare example of a gathering of several talented artists whose collaboration under the guiding vision of a filmmaker results in a unique work of art. Why then, did the film receive such scathing reviews when it was released? It may have been due to the climate of American cinema at the time. Rumble Fish was released in the early 1980's when art films and independent cinema were not as widely celebrated as they are now. Nobody was ready for a stylish black and white film with few big name stars and little sign of mainstream appeal. American critics and studio executives, on the whole, just did not "get it."

It is a marvel that Rumble Fish was even made at all. Only Francis Ford Coppola's unwavering determination and his loyal cast and crew could have made such a project possible. He had the clout and the resources to assemble such a collection of talented people to create a challenging film that acts as the cinematic equivalent of the novel by capturing its mood and tone perfectly. Every scene is filled with dreamy imagery that never gets too abstract but, instead, draws the viewer into this strange world. Coppola uses colour to emphasize certain images, like the Siamese fighting fish in the pet store--some of the only colour in the film--to create additional layers in this complex, detailed world.

After recent lackluster efforts like Jack (1996) and The Rainmaker (1997), it seems that Rumble Fish is Coppola's last, truly personal and experimental film. With a few odd exceptions, he has been content to merely rest on his laurels and reputation and crank out safe, formulaic films that lack any real substance or passion. Perhaps Coppola is tired from the numerous battles he has had with Hollywood studios over the years and simply does not have the energy to make the daringly ambitious films that he made during the '70s and early '80s. It is too bad, because Rumble Fish shows so much promise and creativity. One had hopes that Coppola could continue in this vein and make truly interesting films that constantly challenge its audience.

Copyright (c) 2005 erasing clouds |

|