Of terrorists and men: Aldo Moro's kidnapping in Marco Bellocchio's film Buongiorno, Notte

by anna battista

Darkness. Voices. Darkness. Voices. Behind a door. A voice. A voice behind a door. A man opens a door and enters a flat together with a young couple. He shows them the empty rooms and a balcony that opens on a small garden. He praises every single corner of the big flat, but the young man and woman don't seem very happy, they look rather serious. After a while the estate agent leaves them alone, telling them he's got to go, he's got another appointment. Little does he know that the flat he's just sold will be used as a prison, as the tragic set of a drama that will change Italian history.

Darkness. Voices. Darkness. Voices. Behind a door. A voice. A voice behind a door. A man opens a door and enters a flat together with a young couple. He shows them the empty rooms and a balcony that opens on a small garden. He praises every single corner of the big flat, but the young man and woman don't seem very happy, they look rather serious. After a while the estate agent leaves them alone, telling them he's got to go, he's got another appointment. Little does he know that the flat he's just sold will be used as a prison, as the tragic set of a drama that will change Italian history.

These are the first scenes of the film Buongiorno, Notte (Goodmorning, Night) by Italian director Marco Bellocchio. Based on the book Il Prigioniero (The Prisoner - published in Italy by Feltrinelli) by ex-Red Brigates member Anna Laura Braghetti and journalist Paola Tavella, the film stars Maya Sansa, Luigi Lo Cascio, Pier Giorgio Bellocchio, Giovanni Calcagno, Paolo Briguglia and Roberto Herlitzka.

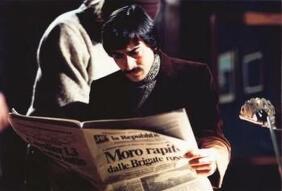

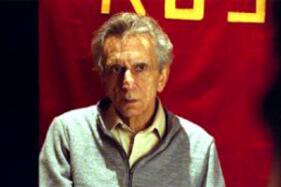

Buongiorno, Notte is the story of Aldo Moro, president of Dc, the Democrazia Cristiana party (Christian Democracy Party), kidnapped in Rome by the terrorist group Br (Brigate Rosse - Red Brigades) on 16th March 1978. To be more precise, the film is not the detailed story of the kidnapping, it's the story of Moro and the terrorists' daily habits, human relationships, small talk, fears and hopes. During the fifty-five days spent in the prison/flat in Via Montalcini in Rome, the only woman of the group, Chiara (Maya Sansa), who officially lives in the flat with her husband Ernesto (Pier Giorgio Bellocchio), but in reality shares it with two other terrorists Mariano and Primo (Luigi Lo Cascio and Giovanni Calcagno) and their prisoner Aldo Moro (Roberto Herlitzka), tries to lead a completely normal life, cooking, doing the washing up and going to work. But behind her ordinary and almost boring life there is another life, the life of the Red Brigades, the life of somebody constantly hiding her real identity from friends and colleagues, who, to reassures herself, has got to constantly check that the kidnapped man is still well-locked up in his tiny prison which only contains a bed and a big flag on which there's written in yellow on a red background 'Brigate Rosse'. Inevitably, little by little, Chiara starts doubting the political cause she's fighting for is a right cause.

Aldo Moro was kidnapped because he had achieved a rapprochement with the Communist party and favoured the official inclusion of the PCI (Partito Comunista Italiano, Italian Communist Party) in the government. During the '70s, Moro was one of the political leaders who gave the deepest attention to the PCI leader, Enrico Berlinguer's project of a so-called Compromesso Storico (Historical Compromise). The leader of the PCI had proposed a solidarity between communists and christian democrats in a moment of serious economical, social and political crisis in Italy, and Moro, then DC president, was one of those who had helped in finding a way to finally form a government of "national solidarity". The BR disapproved of Moro's role and also of the PCI's, because they wanted the latter to keep on being a "militant" party.

But many are the Italians, Moro's family included, who claim the truth about Moro's case has never been found: while he was detained in the BR prison, Moro wrote letters and letters addressed to his family, friends, political allies and colleagues and to the Pope Paul VI. In all the letters Moro stated that the only choice offered to the government in this occasion was to accept the conditions given by the terrorists and negotiate with them. He even provided examples of other cases in which negotiating saved the life of the prisoner. But when Moro's colleagues received the letters, they stated that the man who was writing them wasn't the man they knew. Moro wasn't in his mind, they suggested, because he had probably been drugged up by his kidnappers. Two weeks after Moro's kidnapping, the directorate of Democrazia Cristiana claimed they would have not accepted any negotiation, taking, together with the five main parties that formed the majority of the Italian government, what will later be called a "linea dura" (tough line). Moro's wife, Eleonora, and his family always disagreed with this decision. In answer to the tough line, Moro wrote again, underlining in his last letters that he was sane and wasn't under the influence of the BR when asking the government to negotiate. In his last letters Moro also cursed the Italian political parties who took a tough line accusing them of having condemned him to death.

But many are the Italians, Moro's family included, who claim the truth about Moro's case has never been found: while he was detained in the BR prison, Moro wrote letters and letters addressed to his family, friends, political allies and colleagues and to the Pope Paul VI. In all the letters Moro stated that the only choice offered to the government in this occasion was to accept the conditions given by the terrorists and negotiate with them. He even provided examples of other cases in which negotiating saved the life of the prisoner. But when Moro's colleagues received the letters, they stated that the man who was writing them wasn't the man they knew. Moro wasn't in his mind, they suggested, because he had probably been drugged up by his kidnappers. Two weeks after Moro's kidnapping, the directorate of Democrazia Cristiana claimed they would have not accepted any negotiation, taking, together with the five main parties that formed the majority of the Italian government, what will later be called a "linea dura" (tough line). Moro's wife, Eleonora, and his family always disagreed with this decision. In answer to the tough line, Moro wrote again, underlining in his last letters that he was sane and wasn't under the influence of the BR when asking the government to negotiate. In his last letters Moro also cursed the Italian political parties who took a tough line accusing them of having condemned him to death.

Aldo Moro's kidnapping ended on 9th May 1978, when his body was found in a red Renault R 4 symbolically parked in Via Caetani (in Rome), between Via delle Botteghe Oscure and Piazza del Gesu', the places where the offices of the PCI and the DC were located (to symbolise the rapprochement Moro had carried out between the two parties).

From 1978 on there have been investigations, books, documentaries, conjectures and hypothesis on the Moro case. There have even been a few movies about it, such as Giuseppe Ferrara's Il Caso Moro (1986), based on Robert Katz's book with Gian Maria Volontè as Aldo Moro, and Renzo Martinelli's Piazza delle Cinque Lune (2003).

Both the movies hinted at the conspiracies of the political world which condemned Moro to death. Bellocchio's film is different from this kind of movie because it does not analyse the text of Moro's letters, the unfair reaction of those Italian politicians to whom he had appealed or the Red Brigades' choice of kidnapping Moro. It does not accuse any politician or any terrorist group; it's a movie about those Italian boys and girls who in the '70s joined the Red Brigades in the name of an ideal, a movie about a politician who before being a politician was a man, a husband, a father and a grandfather.

During a press conference for Buongiorno, Notte at the 2003 Venice Film Festival, the director and his cast were given a standing ovation by Italian critics. A few days later, Bellocchio was awarded only the prize for "outstanding individual contribution to the screenplay". There were those who complained about the fact that Bellocchio deserved more prizes, Golden Lion included, and there were those who criticised the award because, since the movie is based on a book written by an ex-terrorist, an award to its screenplay was like an award given to a terrorist. Italian director Mario Monicelli, chairman of the festival jury, dismissed the accusations of not having supported the film by explaining that foreign judges didn't understand the importance of the movie for Italy.

But in the meantime Italians are giving their own special award to Marco Bellocchio since his film is among the top three films in Italian movie charts.

During a press conference for Buongiorno, Notte at the 2003 Venice Film Festival, the director and his cast were given a standing ovation by Italian critics. A few days later, Bellocchio was awarded only the prize for "outstanding individual contribution to the screenplay". There were those who complained about the fact that Bellocchio deserved more prizes, Golden Lion included, and there were those who criticised the award because, since the movie is based on a book written by an ex-terrorist, an award to its screenplay was like an award given to a terrorist. Italian director Mario Monicelli, chairman of the festival jury, dismissed the accusations of not having supported the film by explaining that foreign judges didn't understand the importance of the movie for Italy.

But in the meantime Italians are giving their own special award to Marco Bellocchio since his film is among the top three films in Italian movie charts.

In her sad account of Aldo Moro's kidnapping Il Prigioniero, Anna Laura Braghetti claims that it would have been more dangerous for Italian politicians and Italian politics if the Red Brigades had set Moro free rather than kill him. Marco Bellocchio seems to agree with this claim: rather than showing the body of Aldo Moro in the red Renault as many did, Bellocchio distorts the reality of the kidnapping in Buongiorno, Notte, and shows Moro opening the door of the flat where he has been imprisoned and walking away, happy and smiling, at dawn, while Rome is still asleep.

Buongiorno, Notte is a cathartic movie for Italy, it's a movie in which the ghost of Aldo Moro, which haunted Italian history and the conscience of every Italian for 25 years, has been finally set free.

Copyright (c) 2005 erasing clouds |

|