Cinematic me, cinematic us

by Anna Battista

"Graziosissimo Signore ... voglio dire che vorrei diventare un Grande Artista, per portare alto il mio nome nel Cinematografo Italiano. Guardate le mie fotografie e leggete quello che sono capace di fare. Ginnastica ne so moltissima. Nuoto anche questo lo so. So ballare il tic tac come Fred Staires e anche Danzare. Scuole I avviam. prof. Lingue ne so TRE internazionali Piemontese Italiano e un P'o il Napolitano. Canto un p'o stonato. Musica ne so. Ho già lavorato qualche volta nel teatro del mio Paese. Mi faccia la risposta più prestissimo che può"

"Graziosissimo Signore ... voglio dire che vorrei diventare un Grande Artista, per portare alto il mio nome nel Cinematografo Italiano. Guardate le mie fotografie e leggete quello che sono capace di fare. Ginnastica ne so moltissima. Nuoto anche questo lo so. So ballare il tic tac come Fred Staires e anche Danzare. Scuole I avviam. prof. Lingue ne so TRE internazionali Piemontese Italiano e un P'o il Napolitano. Canto un p'o stonato. Musica ne so. Ho già lavorato qualche volta nel teatro del mio Paese. Mi faccia la risposta più prestissimo che può"

("Dear Sir ... I'm writing because I'd like to become a Great Artist and because I'd like my name to find a place on the wall of fame of Italian cinema. Look at my pictures and read what I'm able to do. I'm very good at gymnastics. I can also swim. I can dance the 'tic tac' like Fred Staires and I can Dance. I attended the first year in a professional school. I know THREE languages, Piedmontese, Italian and a little bit of Neapolitan. I sing slightly out of tune. I can play instruments. I already worked quite a few times for the theatre of my village. Please answer me as soon as you can.")

This is just one of the chancers Ennio Flaiano mentions in the introduction of his collection of reviews Lettere d'amore al cinema (Love Letters to the Cinema). Apart from being written in terrible Italian and being enriched with a few mistakes here and there and apart from rating two dialects, the one spoken in Piedmont and the one spoken in Naples, as two proper foreign languages, the letter addressed to a director shows in tragicomic tones all the eagerness the sender nourishes to become a star and to step into the glittering world of cinema. Flaiano also reports other letters, sent by poor peasants or high school students, the former aspiring to become actors, the latter suggesting the directors buy their insipid screenplays. Though all of them are rather ridiculous in their attempts, they can't be accused, because they have all the same dream, one and only dream which obsessed them: to work for the cinema. A man even begs a director to let him work in Cinecittà, the largest studio in Italy, near Rome, as an actor, but then humbly begs to find him at least a job as a cleaner there, as if by sweeping the place he might have been blessed by the golden dust of those floors. Surely, the naive authors of these letters couldn't have even imagined what was behind the movie business: when the journo Rex Reed asked Ava Gardner if working at MGM was any fun at all she replied "Christ, after seventeen years of slavery, you can ask that question? I hated it, honey. I mean, I'm not exactly stupid or without feeling, and they tried to sell me like a prize hog."

Well, apart from Ava Gardner's comments and from Hollywood's well known fave sport, that of killing stars after creating them, cinema has always had its fans. Because, you know, myths do change, but passions remain the same: Flaiano reviewed The Mouse Hunt (1931) in 1940, stating that children went mad for it. Yesterday it was Mickey Mouse, today it's the Japanese Pokemon. Myths and fame, like the beauty of an actor, are often the results of a particular era and represent the time in which they live; they are documentary, since they mirror the manias of the era and of the culture which surrounds them. Myths do change, but passions definitely remain the same. That is why cinema has still got its allure.

Ennio Flaiano, screenwriter and novelist born in Pescara on 5 March 1910, started to cultivate his passion for the cinema writing reviews of movies almost as if this job were a game. In 1922, he moved to Rome and began writing. Rome became for him the observation post on a whole society and he became one of the protagonists of the local scene and of the group of intellectuals that joined forces around the Caffè Aragno among whom there were Vincenzo Cardarelli, Mario Pannunzio, Vitaliano Brancati and Alberto Moravia. Flaiano started writing after Longanesi's encouragement and in 1947 his first novel, Tempo di Uccidere (Time To Kill), came out. Diario Notturno (1956), Una e una Notte (1959), Il gioco e il massacro (1970), Le Ombre Bianche (1972) followed. He was also the author of five pieces for the theatre collected under the title Un Marziano a Roma e altre farse, and his last works were Autobiografia del blu di Prussia (posthumous, 1974) and Diario degli errori (posthumous, 1977). He worked as a reporter, but he also wrote articles about theatre and cinema criticism. Flaiano's flair for words and his talent at making them sparkle with the power of Edward Lear allowed him to start working in the cinema with Romolo Marcellini in 1942, in 1950 with Federico Fellini and later with Mario Monicelli and Michelangelo Antonioni among the others. In particular, Flaiano worked with Federico Fellini on the screenplay for Lo sceicco bianco (The White Sheik, 1951, with Alberto Sordi, from a Michelangelo Antonioni's subject), La Dolce Vita (1960), La Strada (The Road, 1954), Giulietta degli Spiriti (Juliet of the Spirits, 1965, Fellini experimented LSD under medical control while filming it, here's explained the rich symbolism and visual delights of the movie), Le Notti di Cabiria (Nights of Cabiria, 1957, co-written by Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio Flaiano and Pierpaolo Pasolini for the dialogues), 8 1/2 (1962), Luci del varietà (Variety Lights, 1950). Flaiano also collaborated in 1965 with Erika Mann, daughter of Thomas Mann for the adaptation of the novel Tonio Kroger.

Cinema became his favourite pastime and he unconsciously portrayed in his reviews the image of a nation, Italy, and of its manias from the '50s on. The novelist and screenwriter loved to describe the audience he met when he went to see a movie: he once reviewed Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey and was mesmerised by the monolith revolving in the space, by the red light flooding the screen and especially by the people crowding the cinemas in Rome eager to see what they thought was going to be a sci-fi-cum-erotica fantasy and were highly disappointed when their expectations were met with something rather different. Above all, Flaiano loved tiny cinemas, better than the elegant and huge ones. He would have probably hated the vanity show the media put on every year in Cannes or in Los Angeles.

Cannes 2000: the director Lars Von Trier, of Dogma fame, wins the golden palm with Dancers in the Dark; rock star Bjork, starring in his movie wins as best actress. Honourable prizes go to Jian Wen for Devils on the doorstep, Edward Yang for Yi Yi, Tony Leung for In the Mood for Love and Samira Makhmalbaf for Takhtè Siah among the others. Instead of making constructive criticism about the movies or at least to tell us what the movies were about, the TV spread gossips about Von Trier and Bjork's quarrels on the set and meticulously described the dresses of each of the winners and losers around. The truth is that often in these big media-hyped manifestations, nobody really cares about the movies but us, the audience, who will finally decide if they ever deserve any fame at all. Oh, no, don't worry, we aren't going to rant about Cannes or about fancy clothes now, we are going to rant about how to build a passion for cinema. Yes, because, far away from the Croisette, cinema can well live and be loved. Me? Well, though I love movies, I was never attracted to acting. I remember that once the director Lina Vertmuller was auditioning in my town looking for a girl for her next movie and punters were sent around looking for some chancers and one of the guys suggested I should go and try. "Look, my life is already a genuine drama, I don't need to act in a fake one," was my answer. I'm really too lazy to act, I prefer to watch. And this is proved by the fact that more than a cinema lover, I'm a festival addict, one of those die hard people who might be able to watch movies all day long without ever getting tired. Actually, I am a fanatic of retrospectives and of black and white movies: I once had the stomach to watch a black and white silent edition of The Nibelungs with German subtitles (erm, yes, I still have nightmares...) and I still cry when I watch Charlie Chaplin's sentimental anarchism and heartrending optimism in any of his movies.

"Ohh Heaven. I love the movies. So cool in here. ... Greta Garbo. But I was on a desert island with her. It was a real big island though, and I never saw her except in the movies. How many feelings more at the movies than in life? Garbo looks like looking like looks Garbo... Garbo has Gable Harlow lying down in love at the harbor by a white eye liner. She wanted to do Dorian Grey. She would look into a sheet of metal with a white streak down it. It bored her so much. It bores you tremendously. Shall we do this scene again? ... The thing about really good movies though, ... is it's living without effort ... I'm a person here in this movie theatre, in the darkness ... like a worm in a heart" - Richard Hell, "The Voidoid"

But if the passion to become an actor often is helped by watching movies and is then developed by years and years studying dramatic arts, passion for cinema often spreads in movie theatres or...in museums. "Good morning", Davide Campolieti, responsible for the museum of cinema in Pescara, the MediaMuseum, quietly greets me on a bright and sunny morning. The first thing which salutes me as I step into the museum are the many huge movie posters stored here. Most of them are the Italian versions of old American movies, mostly from the '50s and '60s. On the bigger wall in front of me there is I Gladiatori, directed by Delmer Daves, nothing to compare to today's "Gladiator", starring Russell Crowe, fighting in an electronic Colosseum, so Lara Croft style and so historically wrong. Other posters attract my attention: Le Amanti (Projection Privée) with Jane Birkin, music by Serge Gainsbourg: it looks very "lounge" if I can say so; Ad Est di Sumatra by Budd Boetticher; Sette Volte Donna by Vittorio De Sica with Peter Sellers and Vittorio Gassman; La Regina D'Africa (The African Queen, 1951) with Humphrey Bogart and Katherine Hepburn; L'Assoluto Naturale by Mauro Bolognini and with Ennio Morricone's music; E Se Per Caso Una Mattina by Vittorio Sidoni and also with music by Ennio Morricone; Il Terzo Uomo (The Third Man) with Orson Welles and Alida Valli; Amleto (Hamlet) by Lawrence Olivier which Flaiano praised in a review in 1949; Identikit with Elizabeth Taylor. The posters look funny, all painted in hard brushes, with very harsh colours, they seem centuries away from today's perfect posters.

The museum has just two large rooms with the exhibitions and two other rooms which host the archives. Not a huge museum at all, but often treasures can be find in a casket and this is obviously the case. "The MediaMuseum opened on 11th March 2000. The idea to open it came with the 100th Anniversary of cinema in 1995," Davide explains me, "In the summer of that year it was organised in Pescara en exhibition in the building of the former university. The exhibition was then moved to Vasto in September 1995, but at the end of that year, Edoardo Tiboni, the President of the Flaiano Association and of the Istituto Scrittura e Immagine, suggested to open a proper permanent Museum of Cinema which gave particular attention to the cinema made in this region, Abruzzo, shot in Abruzzo, made by the local inhabitants or which had any connections with the region." And here can in fact be seen pictures of movie shot in Abruzzo, from Rutger Hauer in LadyHawke to Harvey Keitel in Cop Killer by Roberto Faenza. In the second exhibition room there are Manfredo Acerbo's original sketches. Born in Pescara in 1913, Acerbo started painting wall posters for movies during the '40s, signing his works as Manfredo, to distinguish his non-cinematographical paintings which he signed with his surname. Among his manifestos are those for the movies I Magliari, Europa di Notte, Il Mulino del Po, La Tunica, Il Processo, Queimada. In 1954 he won the Premio Spiga Cambellotti as best cinematographic Italian painter. He died in Rome in 1989. "Manfredo Acerbo's sketches are the most important and exclusive exhibit we have here at the museum. His wife donated almost all the wall posters on the day of the opening," Davide explains. The sketches are all in bright colours, but there is one in particular, the one for Candy e il Suo Pazzo Mondo which attracts my attention. This '60s movie, Candy, featured Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, Marlon Brando, Charles Aznavour and Ringo Starr among the others, and it was an adaptation of the novel by same title written by Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg and published in 1958 by Maurice Girodias' controversial Olympia Press in Paris. The sketch for the Italian poster of this movie shows female figures scantily dressed: the painter even used pieces of the wraps of a local type of cake called Parrozzo for the bikini of one of the figures. It is as if Acerbo couldn't find any colour which fitted the ideas which came out of his coloured mind and finally found the right inspiration and the material in something from his home town, a cake which was also desperately loved by Gabriele D'Annunzio.

Well, I've just mentioned D'Annunzio and I only have to turn to the opposite wall to admire posters and pictures of Cabiria (1914, directed by Giovanni Pastrone). Poet and novelist Gabriele D'Annunzio wrote the subtitles for this silent movie: the poster shows a naked woman being held over burning flames by a pair of hands. Its opulent scenarios are almost pompous and pretentious. So, to take a little distance from this baroque movie, I pass to the section dedicated to Ennio Flaiano. There are quite a few movies listed here which Flaiano collaborated to or co-wrote: I Vitelloni (1953), Roma Città Libera (1948, directed by Marcello Pagliero and featuring Vittorio de Sica) which won the Nastro D'Argento for the screenplay; Tempo di Uccidere (1989, directed by Giuliano Montaldo, starring Nicolas Cage and taken from Flaiano's novel); 8 1/2 (1963, nominated to the Oscar in 1964 for the screenplay); La Dolce Vita (also stored at the museum is its screenplay) with that unforgettable picture of Anita Eckberg, la femme fatale who takes a midnight bath in the Trevi Fountain in Rome, her black dress contrasting with the virginal white marble of the statues, and the documentary Oceano-Mare shot with Anderman for the Italian TV. Among the various pictures taken on the various sets, there's one I like so much: it shows Ennio Flaiano, Federico Fellini and Anita Eckberg at the time of shooting La Dolce Vita. Before passing on I decide that I love this picture because it shows a more relaxed version of the mad director and the fatal woman, smiling to each other like ordinary people and not behaving like the huge myths they are in my fancy. La Dolce Vita, directed by Federico Fellini in 1959 and co-written with Ennio Flaiano in 1958, was booed in Milan, but awarded in Cannes and starred Marcello Mastroianni as the tabloid reporter who sees his life in shallow Rome society as worthless (interesting note: in La Solitudine del Satiro, 1973, Flaiano remembered how was difficult to find a name for the reporter of La Dolce Vita. In that period he had been reading George Gissing's travel book By The Ionian Sea, in which the novelist reports a visit at the Albergo Centrale, in Catanzaro, in December 1897. Gissing reported the name of the owner of the hotel, Coriolano Paparazzo, who put notes on the doors of the various rooms telling his guests how much he was disappointed at the fact that some guests were having their meals in other establishment than his own. Flaiano adopted the same name for his photographer because he liked it so much).

And talking about myths, above the picture featuring Fellini, Eckberg and Flaino, there are a few photographs of the novelist and screenwriter John Fante: we can spy him in LA on Van Ness Avenue, in his office in Hollywood or in his house in Malibu and finally in Roseville in his parents' house. "All the Fante pictures are from the late '50s and they are unpublished," Davide explains. The museum seems to have a particular respect for the Fante household: John Fante's son, Dan, author of the novels Chump Change and Mooch, visited the museum in August and donated to it his play Don Giovanni. Here there is also the poster for Il Re di Poggioreale by Duilio Coletti behind which there is a Fante story: while Fante was in Italy he was supposed to write the movie Navarra, King of Naples, which survived with another title Il Re di Poggioreale, with a screenplay by John Fante, Vittoriano Petrilli and Giuseppe Mangione and directed by Duilio Coletti in 1961. Apparently, one scene of that movie is from Fante, the scene of the rescuing of the treasure of San Gennaro and of the liquefaction of the blood. Fante wrote to his wife on 13 September 1960 saying in fact that he would have gone to Naples on 19 September "to watch the ceremony of the liquefaction of the blood of San Gennaro which is an integral part of our story."

Stories. That's what's behind everything here, behind every picture, every poster and every line of screenplay. Stories like the love story between Giulietta Masina and Federico Fellini, here portrayed on the set of Giulietta degli Spiriti. Stories of prizes like the one showed in the pictures taken at the ceremonies of the Flaiano Awards and other stories. Stories, like the one hid in a picture taken in 1948 at the Caffè Greco in Rome: Orson Welles, Ennio Flaiano e Vitaliano Brancati can be spotted among the others sitting around. The brotherhood of the fame, the brotherhood of the people who in the '50s met in Rome, wrote and dreamt.

"Mario Pannunzio and Leo Longanesi had a decisive importance for me because they gave me the means to allow me to write. And I must add, they gave me the means to write about things I didn't even know. The only way to protest against fascism, was not to talk about the actual events, but about other things. The movie critic was some guy who couldn't understand anything about cinema, but he went to the cinema and wrote his article about it talking about something else. That was the only way to protest against fascism": Ennio Flaiano.

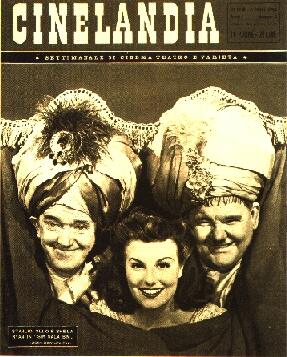

I quietly peep through the glass cases in the middle of the largest room of the museum and, apart from the 'Hollywood-spoken-cinema-stars-killed-the-silent-cinema-star' "Sunset Boulevard" screenplay signed by Billy Wilder, I find something morally debating and also disgusting, but still important to witness the censorship applied to the cinema during fascism. Under austere screens, photocopies and documents of a darker era are displayed, they are from 1941 and they state that pictures, articles and news about foreign actors such as Fred Astaire, Charlie Chaplin, Bette Davis and also about the Metro Goldwyn Meyer can't be published. While another telegram sent to the prefects by the minister Fernando Mezzasoma forbids Jew artists belonging to the theatre or the cinema to carry on their activities. I shake my head at the absurdity of it all and to recover from the inane stupidity of that period I indulge in flipping through the pages of an old pack of the short-life sugar-coated magazine Cinelandia, the magazine which Flaiano directed before passing to Il Mondo. Like a lot of magazines of those times, Cinelandia was blessed by serious articles such as interesting movie reviews, articles on music such as those on the Jazz clubs in Rome, articles by personalities of literature such as William Saroyan, together with more bland and vapid stuff like what looks like hilarious adverts for a fancy brand of orange juice. Cinelandia featured gossips about all the stars of those years from Rita Hayworth to Ingrid Bergman and Ester Williams from Macario to Anna Magnani, the fierce actress, born in Egypt by Italian mother and Arab father, who brought on the screen her anger and weakness, her aggressiveness and sweetness.

I quietly peep through the glass cases in the middle of the largest room of the museum and, apart from the 'Hollywood-spoken-cinema-stars-killed-the-silent-cinema-star' "Sunset Boulevard" screenplay signed by Billy Wilder, I find something morally debating and also disgusting, but still important to witness the censorship applied to the cinema during fascism. Under austere screens, photocopies and documents of a darker era are displayed, they are from 1941 and they state that pictures, articles and news about foreign actors such as Fred Astaire, Charlie Chaplin, Bette Davis and also about the Metro Goldwyn Meyer can't be published. While another telegram sent to the prefects by the minister Fernando Mezzasoma forbids Jew artists belonging to the theatre or the cinema to carry on their activities. I shake my head at the absurdity of it all and to recover from the inane stupidity of that period I indulge in flipping through the pages of an old pack of the short-life sugar-coated magazine Cinelandia, the magazine which Flaiano directed before passing to Il Mondo. Like a lot of magazines of those times, Cinelandia was blessed by serious articles such as interesting movie reviews, articles on music such as those on the Jazz clubs in Rome, articles by personalities of literature such as William Saroyan, together with more bland and vapid stuff like what looks like hilarious adverts for a fancy brand of orange juice. Cinelandia featured gossips about all the stars of those years from Rita Hayworth to Ingrid Bergman and Ester Williams from Macario to Anna Magnani, the fierce actress, born in Egypt by Italian mother and Arab father, who brought on the screen her anger and weakness, her aggressiveness and sweetness.

Davide explains me how to visit the museum "We've already had quite a few visitors, especially students and people with a particular interest in the history of the cinema or in Ennio Flaiano and Gabriele D'Annunzio. The students who visited our premises also used the videos stored in our archives. There are in fact two types of visits you can make here at the museum: a traditional one, just having a look around and admiring the various pictures and explanations or a more interesting one, reading the magazines, surfing the Internet, watching DVD or videos. We have around 3000 titles between Italian and foreign movies, documentaries and original shortcuts. The Istituto Scrittura e Immagine is also responsible for the Festival del Cortometraggio (Shortcut Festival), so here at the MediaMuseum we hold the archive of it and of the Festival Internazionale del Lungomatraggio (International Festival of the Feature Film). Unfortunately, we still haven't a proper soundtrack archive. We hope to move from here and find a proper place to establish the museum since we have pictures of particular dimensions which should be exhibited in proper spaces and there should be a few rooms dedicated to the exhibitions while books, magazines and documents might be read or interactive points browsed in other rooms."

Yes, that would be a great idea, moving to larger premises and build up also a soundtrack archive where, the visitor might find, among the other stuff, more Ennio Morricone and his western or loungy stuff or his uptempo La Corta Notte delle Bambole di Vetro, possibly sang by Edda Dell'Orso. An archive where Luis Bacalov's scores might be listened to as well. Bacalov, Argentine soundtrack composer who won the Oscar for the movie The Postman (directed by Michael Radford) in 1995 and the Premio Rota in 1996, received a prize for his career in Pescara in October 2000. Luis Bacalov, who among the other soundtracks wrote the score for the movies Il Vangelo Secondo Matteo (1965, Pierpaolo Pasolini), La città delle Donne (1980, Federico Fellini) and for the movie taken from Primo Levi novel, La Tregua (The Truce, 1997, directed by Francesco Rosi, with John Turturro), thinks that soundtracks are very very important and while in Pescara to receive his prize, the maestro explained his audience the difference between writing a personal composition and the score for a movie: "The basic difference between a personal piece of music, such as a track written for an orchestra, composed risking to choose particular styles instead of others, and writing the scores for a movie is that a movie is the result of the work of a team of people. Those who don't accept this truism, don't work well in the movie business, indeed there were great musicians who rebelled against this principle. Silent movies were different because composers were free to do whatever they wanted to do. Now, with the spoken cinema things are different and a musician must take care of what the director says: sometimes this is difficult because musicians and directors are both arrogant and narcissistic and actually I myself refused working with a few directors because I couldn't get along with them. Finally, what we must take care of is that the movie is not a product of the director, but a movie belongs to everyone, to the director, the producer, the musician and so on because each of them worked for that movie." Soundtracks are really important, that's why there should be in the museum a room where Peter Thomas might be listened in all his glorious jazzy spaced splendour, possibly while watching some weird video or shortcut and possibly with a cocktail in your hand or a room where you might listen not only to David Holmes' proper soundtrack for the Steven Soderbergh movie Out of Sight, but also to his other cinema-inspired albums This Films Crap Lets Slash The Seats, Lets Get Killed and the latest Bow Down To The Exit Sign, based on a script by Lisa Barros-D'Sa, after all in his first 1993 single "De Niro", Holmes even sampled Morricone, showing a genuine passion for cinema. Wait, wait, I've got a great idea: an archive of songs sang by actors and an archive of songs dedicated to movie stars and directors: Uschi Glas and Nico's stuff would be there and then Mogwai's scary and dark "Kubrick" and Geneva's soundscape "Morricone" among the others and then yes, erm, I know, I'm digressing. So, after going back on planet earth, I ask Davide about the future of the museum "Our plans for the future include establishing a lab. We have shooting and cutting equipment and we are going to give our visitors and especially to students, the chance to use our equipment to shoot a documentary, a shortcut or to produce whatever they want to produce. Moreover, we are planning to start from October seminars and lessons held by historians and critics, personalities connected with the world of cinema. Obviously, the classes will be hold here in these rooms, in the museum, and we'll also organise video forums, proper cycles of movies since we do have video projectors and are able to project movies on the big screen."

So, you see, it doesn't matter who you are or what you like to watch on the screen: are you going to see yesterday's cheap erotica Emmanuelle (1973) by Just Jaekin or Julien Temple's punky The Filth and The Fury, the most recent Sex Pistols' documentary finally expurgated of Malcolm McLaren's presence? It doesn't matter: just go and enjoy yourself. Have a cinematic holiday and make way for those images you'll see on the big screen to stick to your brain like cinematic tattoos.

Ennio Flaiano was so obsessed about cinema that he never managed to concentrate on writing proper novels, and whenever he wrote he always introduced in his stories characters who were screenwriters or had some kind of connection with the world of the movies: the protagonist of Melampus is a failed screenwriter looking for an inspiration in the States; the protagonist of Adriano goes to pay a visit to a friend who is a director shooting a scene of a pilgrimage in the neighbourhoods of Rome. Flaiano wrote tons of reviews and screenplays, still, he recommended young people who wanted to write, never to write screenplays. He thought in fact that anyone could write good books, except screenwriters and journalists and that, after working as a screenwriter, one would have had to change his interior dimension to apply again to writing a novel. Flaiano loved the realistic movies, but, later, he ended up hating realistic movies and fantastical ones as well, so he went out looking for something different, something which would have arisen in the audience another state of wonder, the state of the dreams and of the art. He never found it. Beware then, screenwriter, director, actor, producer, soundtrack composer, reviewer or simple movie goer and cinema lover, whatever you choose to be, you might find that metaphysical road and arrive where Flaiano never got: the trick is to keep being passionate about cinema and to keep open "The Gates to Film City" as the title of that glorious track by Future Pilot AKA Vs Two Lone Sworsdsmen says.

Copyright (c) 2005 erasing clouds |

Photo taken in the MediaMuseum, a museum devoted to cinema, in Pescara, Italy. |